Introduction: The High Cost of “Grade B”

In the modern knitting mill, the difference between a profitable quarter and a financial loss often hangs by a single thread literally. For a standard circular knitting setup running 30s Ne (20 Tex) cotton at 25 RPM, the production volume is immense. However, volume is irrelevant if the output is classified as “Grade B” or “Seconds.” With global profit margins in basic knits often compressing below 5%, a defect rate exceeding 2% destroys the competitive advantage of even the most efficient floor.

Quality cannot be inspected into the fabric at the finished stage; it must be engineered into the loop formation process. When a high-speed machine producing Single Jersey hits a snag, it isn’t just wasting material; it is wasting energy, labor, and machine-hours that can never be recovered. The cost of a fault is not just the price of the yarn; it is the opportunity cost of the Grade A fabric that should have been produced in that time slot.

To combat this, we must move beyond blaming the operator and look at the interaction between the machine mechanics and the material physics. This guide serves as a diagnostic tool to bridge that gap.

Executive Summary: Key Takeaways

- The Financial Ratio: The cost of remediating a fault downstream (dyeing/finishing) is 10x higher than catching it at the knitting head.

- The “Trinity” of Causes: Faults generally stem from three roots: Machine State (Mechanics), Yarn Quality (Material), or Ambient Conditions (Humidity/Lint).

- Standardization: A mill without documented tension standards and cam settings is not a factory; it is a casino. ISO 9001 practices must be adopted for quality improvement.

Understanding the gravity of these losses sets the stage for the technical deep dive. However, the most immediate and visible threats to fabric quality usually originate right where the metal meets the yarn: inside the cylinder.

The Vertical Nightmares: Needle & Sinker Faults

Since the cylinder is the heart of the operation, it is no surprise that the most persistent defects manifest vertically, tracing the exact path of the metal components involved in loop formation. When the interaction between the needle and the cam track is compromised, the fabric immediately displays the evidence in the form of longitudinal lines or subtle striations.

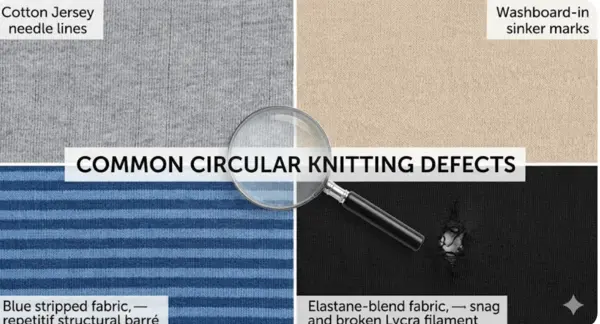

Vertical Lines (Needle Stripes) This is the single most common fault in circular knitting. It appears as a continuous or intermittent vertical line where the stitch formation is irregular compared to the adjacent wales.

- The Diagnosis: A sharp, distinct line usually indicates a mechanical deformation of the needle. This could be a bent latch, a stiff latch (preventing proper clearing), or a sheared hook.

- The Remedy: Operators often just change the needle, but the Technologist must ask why the needle failed. If multiple needles fail in the same trick, the cylinder trick wall may be damaged, or impacted lint is forcing the needle out of alignment.

- Technical Check: Ensure the needle requires minimal force to slide in the trick. A tight needle creates friction, generating heat that can exceed 80°C (176°F), fusing synthetic fibers and snapping latches.

Sinker Marks While needle lines are distinct, sinker marks are more insidious. They appear as vertical “washboard” effects or blurred lines, often visible only when the fabric is held against the light.

- The Diagnosis: This typically stems from improper sinker timing or a worn sinker nose. If the sinker releases the loop too early or too late relative to the needle’s descent, the stitch structure distorts.

- The Remedy: Check the Centralization of the cylinder. If the cylinder is not perfectly centered with the dial, the sinker loop length will vary around the circumference.

- Precision: Standard tolerance for cylinder centralization should be within 0.03mm to 0.05mm. Any deviation beyond this on a fine gauge machine (e.g., 28GG) will result in visible striations.

While vertical faults are usually mechanical and isolated to specific wales, horizontal faults pose a greater threat because they affect the entire circumference of the fabric tube. These defects often blur the line between machine settings and raw material quality.

The Horizontal Headaches: Barré & Yarn Variation

While vertical faults are usually isolated to specific machine components, horizontal faults pose a far greater commercial threat because they affect the entire circumference of the fabric tube. Among these, Barré (or Barre marks) is the most contentious defect in the industry, often sparking the “Blame Game” between the Knitting Master and the Yarn Spinner.

Structural Barré (The Machine Fault) This appears as a repetitive horizontal stripe caused by physical differences in loop geometry.

- The Diagnosis: If the repeating pattern of the stripes aligns perfectly with the number of feeders on the machine, the issue is almost certainly mechanical.

- Root Cause: It typically stems from uneven Stitch Cam settings. If Feeder 1 is drawing a loop length of 2.9mm and Feeder 2 is drawing 3.1mm, the resulting fabric will reflect light differently, creating a shadow line.

- The Remedy: Conduct a “Course Length” test immediately. Use a Yarn Speed Meter to ensure every feeder consumes the exact same length of yarn per revolution.

- Tolerance: Variation between feeders should strictly be kept below ±2%.

Yarn Barré (The Material Fault) When the machine settings are perfect but the stripes persist, the fault lies in the material.

- The Diagnosis: These stripes often appear random or lack the rhythmic consistency of structural barré.

- Root Cause: This occurs when yarn lots are mixed. Even if both yarns are labeled “30s Ne Combed,” a slight variation in Micronaire (fiber fineness) or Twist Per Inch (TPI) will cause the dye uptake to differ. A variation of just 0.1 Micron can lead to visible shade variation after dyeing.

- The Remedy: Strict inventory control. Never mix lots on the same machine creel. If mixing is unavoidable, alternate the cones (e.g., 1 New, 1 Old) to blend the error, though this is a risky salvage operation.

Tension Lines Sometimes, the issue isn’t the yarn itself, but how it is fed.

- The Focus: The Positive Feed (MPF) belts. If a belt is slipping or worn, the yarn delivery speed drops, creating a tight row of stitches.

- Standard: Input tension for cotton yarns should generally be maintained between 2g to 5g. Anything higher risks distorting the loop structure before it is even formed.

Solving the Barré puzzle usually clears the biggest hurdle in basic knitting. However, modern fashion demands stretch, introducing a volatile variable into the equation: Elastane.

The Elastomeric Challenge: Lycra & Plating Faults

Solving the Barré puzzle usually clears the biggest hurdle in basic knitting. However, modern fashion demands stretch, introducing a volatile variable into the equation: Elastane (Spandex/Lycra). Introducing a filament yarn alongside spun yarn requires a delicate balancing act known as “Plating,” where the margin for error is microscopic.

Lycra Breakage in circular knitting When the elastomeric yarn snaps, the fabric loses its recovery immediately, leading to “rot” or sagging sections.

- The Diagnosis: Inspect the break point. If the Lycra end is “fluffy” or frayed, it indicates abrasion (rubbing against a rough surface). If the end is sharp/clean, it indicates excessive tension snap.

- Root Cause: Often, this is a pathing issue. A microscopic groove cut into a ceramic guide or a rusted feeder eyelet acts like a razor blade against fine denier Lycra.

- The Remedy: Replace metal guides with Ceramic or Alumina-Oxide guides at high-friction points. Check the Draft Ratio. A standard draft for single jersey is often 1:2.8 to 1:3.2. Exceeding this stretches the filament beyond its elastic limit.

Miss-Plating (Grinning) In a perfect plated fabric, the Lycra sits on the back (technical back), and the cotton sits on the face. Miss-plating occurs when the Lycra slips to the front, creating a shiny, “glittery” defect on the matte cotton surface.

- The Diagnosis: The Lycra is not being held in the correct position relative to the ground yarn during loop formation.

- Root Cause: Incorrect Feeder Positioning. The Lycra yarn carrier must be positioned closer to the needle hook and slightly higher than the ground yarn carrier to ensure the ground yarn covers it.

- Unit Standard: Tension control is critical. For 20 Denier Elastane, the input tension should be roughly 4cN to 6cN. If the tension is too low, the yarn goes slack and “grins” through to the face.

Managing these sensitive yarns requires precise instrumentation. However, there is a dangerous assumption that modern technology eliminates the need for human oversight—a belief that leads us directly to a common industry pitfall.

The Common Myth of Circular Knitting

Managing these sensitive yarns requires precise instrumentation. However, there is a dangerous assumption that modern technology eliminates the need for human oversight—a belief that leads us directly to a common industry pitfall.

The Myth: “If we have sophisticated electronic positive feeders (like Memminger-IRO) installed, we don’t need to manually check yarn tension.”

The Reality: Electronic feeders are excellent at maintaining yarn speed, but they are not immune to physics. The “Set and Forget” mentality is a silent quality killer.

While an MPF unit ensures the yarn is delivered at a constant rate, it cannot account for what happens after the yarn leaves the wheel.

- The Blind Spot: If a ceramic eyelet between the feeder and the needle is clogged with paraffin wax or lint, the tension at the needle point will spike, even though the feeder is running perfectly.

- The Drift: Feed belts wear out. A belt that has lost 1mm of thickness due to abrasion will drive the wheel slightly slower than a new belt, creating a tension variance between feeders that the sensor might not flag.

The Technologist’s Rule: Trust the machine, but verify with the handheld tension meter. A manual tension audit should be mandatory at the start of every shift, not just when a fault appears.

Even with perfect tension and flawless mechanics, the mill environment itself can conspire against quality. This brings us to the “gritty” reality of contamination.

The Reality : Troubleshooting Logic

Even with perfect tension and flawless mechanics, the mill environment itself can conspire against quality. This brings us to the “gritty” reality of contamination and mechanical stress—faults that are often misdiagnosed as dyeing issues.

Oil Stains: The Line vs. Spot Rule Oil is necessary for high-speed circular knitting (needles move at ~1.5 m/s), but it is a contaminant if it reaches the fabric.

- The Diagnosis: The shape of the stain tells the story.

- Vertical Oil Lines: If the oil appears as a continuous or dashed vertical streak, it is a Machine Leak. The cylinder oil seal may have failed, or the automatic lubrication system is over-dosing, forcing oil out of the trick walls.

- Random Spots: If the stains are blotchy and random, it is usually Handling Contamination. This often happens during doffing (unloading the roll) or from dirty transport trolleys.

- The Check: Use a UV (Black) Light. Knitting oils often contain additives that fluoresce. If the stain glows under UV, it’s needle oil. If not, it might be grease from a floor trolley or external dirt.

Star Marks (Crow’s Feet) This is a stress fault that looks like tiny, star-shaped puckers or creases in the fabric.

- The Diagnosis: These marks are physically distorted loops that do not relax back into shape.

- Root Cause: Excessive Take-Down Tension. While the knitting head forms the loop, the take-down rollers pull the fabric down. If this pull is too aggressive—especially on delicate fabrics like Micro-Modal or Viscose—the loop structure is permanently deformed.

- The Remedy: Lower the take-down tension immediately. The fabric roll should be firm, but not “rock hard.”

Fly Contamination

- The Issue: Foreign colored fibers (e.g., red lint floating into a white cotton lot).

- The Remedy: This is a housekeeping failure. Isolating knitting zones with curtains and ensuring overhead traveling cleaners (blowers) are timed correctly is the only defense.

Fixing these faults requires time and money, but ignoring them costs more. This leads us to the final calculation every circular knitting mill owner must make.

The ROI of Preventive Maintenance

Fixing these faults requires time and money, but ignoring them costs more. This leads us to the final calculation every mill owner must make: the price of prevention versus the cost of correction.

In the textile industry, the most expensive phrase is “Run to Failure.” Many mills hesitate to replace a full set of needles or sinkers until they physically break, viewing spare parts as a pure expense. This is a false economy.

The Math of Meltdown Let’s break down the cost of a single “Needle Line” fault on a 30-inch diameter machine running at 25 RPM.

- The Incident: One needle latch shears off. The machine runs for 1 hour before the operator or the quality inspector catches the defect.

- The Loss: At roughly 15 kg/hour production, you have produced 15 kg of “Seconds.”

- Cost of Yarn (Cotton Combed): ~$4.50/kg x 15 kg = $67.50.

- Knitting Cost (Energy + Labor): ~$0.50/kg x 15 kg = $7.50.

- Total Loss: $75.00.

- The Prevention: The cost of a high-quality German or Japanese needle for circular knitting machine is approximately $0.40 to $0.80.

The Ratio: You risked $75.00 of product to save $0.80 on a part. When you multiply this by a 50-machine shed, the financial leakage is catastrophic.

Predictive Replacement Strategy Smart mills adopt a “Life-Cycle” approach.

- Guideline: Instead of changing needles individually as they break (which causes constant machine downtime and fabric start-marks), replace the entire cylinder set after a fixed period (e.g., 6 months or specific machine revolutions), regardless of their apparent condition.

- The ROI: While the upfront cost of 2,000+ needles is high, the sudden jump in “First Quality” efficiency (often rising from 88% to 98%) recovers that investment within weeks.

Ultimately, machinery can be repaired, and yarn can be replaced, but reputation is non-renewable.

Conclusion: The “Legacy” of First-Time-Right

Ultimately, machinery can be repaired, and yarn can be replaced, but reputation is non-renewable. In a global market where buyers in Europe or the US can switch suppliers with a single email, consistency is the only currency that matters. A mill that consistently delivers “Grade A” fabric does not just sell a commodity; it sells the peace of mind anchored in ISO quality standards.

The transition from a “Repair Shop” mentality to a “Zero-Defect” culture is not easy. It requires empowering the knitting technician to stop a machine before a fault occurs, rather than scolding them after the fact. It requires viewing the cost of top-tier needles and precise tension meters not as overhead, but as insurance.

Fabric faults are the silent language of the machine telling you what is wrong. The question is not whether the machine is speaking, but whether management is listening. In the end, the most profitable fabric in the world is the one that is knitted right the first time.